This is a slightly revised translation of an essay I wrote for the festschrift in honour of Willem Kuiper, reader in Dutch medieval literature at the University of Amsterdam (Want hi verkende dien name wale, ed. M. Hogenbirk & R. Zemel). Willem has done more than any scholar to raise our awareness of names in medieval texts; this essay is presented in the spirit (although not with the erudition) of Willem’s always fascinating and thought-provoking columns, published since 1993 in Neder-L (http://nederl.blogspot.co.uk).

Years ago, on holiday in Italy, I met two Danes who lived in Venice, where they sold tickets for concerts, wearing period costume. They told me that for months they had announced tickets for performances of music by ‘Vivaldi, Albinoni, Anonymus and Verdi’. Only after a long time had they realized that Anonymus was a composer of a completely different calibre from the other three.

Besides being a famous composer of classical music, Anonymus (also known under her pseudonym Anonyma) was hands down both the most versatile and most productive author of the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, scholars have never held Anonymus in very high esteem: in general, they prefer a different name for the author of ‘their’ texts. The wish to know more about these texts leads to a desire to label every text with an author’s name. When, after long puzzling and archive research, that desire can finally be satisfied, scholars often breathe a ‘sigh of deceit’, as Herman Pleij, professor of Dutch medieval literature, once fittingly characterized it (in a slip of the tongue which he subsequently himself branded Freudian).

Of course, to some extent, this was already the case in the Middle Ages, and even then people often searched for the name of the author behind the anonymous text. Works by Anonymus could with regularity be given now this, then that author’s name – thus, for example, in the case of the Historia Brittonum, which was sometimes attributed to the all but unknown Nennius, but at other moments to the famous Gildas. In the meanwhile, the text also continued to be copied as a work by Anonymus (see Dumville 1975/6).

An author’s name could also fulfill a function which could perhaps best be compared to the function of the publisher’s logo on the modern printed book: at the same time a mark of quality and an indication of genre. Thus, when Geoffrey Chaucer had prematurely ceased writing the Canterbury Tales, many an Anonymus wrote continuations under Chaucer’s name (see Bonner 1951). Even that collective authorship, by the way, did not suffice to tell all the tales promised on the departure to Canterbury. Similarly, the ‘father of all Dutch poets combined’, Jacob van M(a)erlant – let’s not even get started about the correct form of his toponym – appears to have been a victim of such practices with some regularity. Which regularity exactly is still subject of dispute, but dBoec vanden Houte (‘The Book of the Rood’) has long ago been deleted from his oeuvre, and the same should happen with Van den lande van oversee (‘Of the Land Oversea’, see Jacob 2000). Der kerken clage (‘Complaint of the Church’) and some of the Martijns attributed to Jacob are also suitable candidates for such deletion.

Name grab still regularly occurred in the early modern period, too: thus, six years after his death, Shakespeare wrote a play about Merlin (it was first printed much later still, in 1662). Even when taking into account the time-bending powers of the prophet who was the subject of the play, this is an impossible achievement of the bard. And thus it continues: still in the nineteenth century a fabricated eye-witness account of the trial and execution of Jerome of Prague was published under the name of the actual eye-witness Poggio Bracciolini (see Salomon 1956).

Comparable to such cases is also the pseudo-Author, or perhaps better the pseudo-Authority: an Anonymus who presents as a usually many centuries older (late) classical authority. The Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle (Dunphy 2010) names, among others, pseudo-Joshua de Stylite, pseudo-Methodius, pseudo-Iamsilla and pseudo-Symeon. Willem Kuiper has introduced his readers to, among others, pseudo-Turpin, pseudo-Bonaventura, pseudo-Hegesippus and pseudo-Albertus Magnus (Kuiper 2007, 2010, 2013; Kuiper & Resoort 1995; Lie, Kuiper & Summerfield 2011). And there are also pseudo-Texts: thus, Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that behind his Latin history of Britain lay a ‘British’ (that is, probably, Welsh) source. His actual use of sources tells another story (see Levelt 2002). Possibly most impressive in this context is the work of Annius of Viterbo (which appropriately itself again is a pseudonym of Giovanni Nanni). In his work pseudo-Authority and pseudo-Text coincide: to support his pseudo-Ancient History, Annius himself composed seventeen complete pseudo-Works by pseudo-Authors (see Ligota 1987).

But while there are, of course, many texts which were provided with an author’s name in this way, and on the other hand enough texts of which the author’s name was known with reasonable certainty, the medieval public in general did not object against work by Anonymus – and Anonymus was always ready to satisfy the desires of that public. Many of the most famous works from the Middle Ages are transmitted to us anonymously: from Beowulf to the Brut chronicles, from Everyman to Piers Plowman,* from the York Mystery Plays to the Dream of the Rood, from Pearl to Patience to Cleanness to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, time and again the texts were written anonymously and remained so, or were only provided with an author’s name (much) later. The following example will make clear how that process of attribution is not always innocent, and that in any case the moment of attribution of authorship is also a moment of significant loss.

In 1517, in Leiden, Die cronycke van Hollandt, Zeelandt ende Vrieslant (‘The Chronicle of Holland, Zeeland and Friesland’) was published. The printer was Jan Seversz, the author was Anonymus. An argument has been made that the author did not wish to reveal his identity because the work contained some ideas which were ‘quasi-Lutheran avant la lettre’, but here as always the law of Ockham’s razor applies: the inquisition, self-evidently, was not introduced ‘avant la lettre’. In 1516, when the author submitted the manuscript of the chronicle to the publisher, virtually nobody had ever heard the name Martin Luther in the Low Countries (only in October 1517 he would publish the theses which would make his name renowned and much maligned), and religious persecutions only really took off over the course of the 1520s. That the chronicle’s publisher, Jan Seversz, in 1524 became the first Dutch printer to feel the brunt of these persecutions does not change that: Anonymus is not Merlin, and cannot foresee the future. When the chronicle was written, one would be entirely justified to say: ‘Nobody expects the Spanish inquisition.’ Anonymus remained anonymous because that was the matter of course; there is, therefore, no need to search for extraordinary circumstances to explain that anonymity.

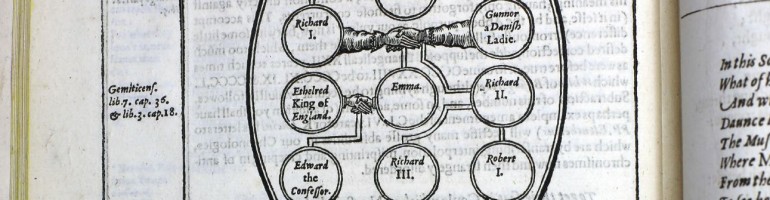

The title of the chronicle, as well, was as generic as could be. Quickly, however, it was replaced by readers with more specific descriptions: the ‘large’ chronicle of Holland; the chronicle with ‘divisions’ (the work was organized in thirty-two ‘divisions’). Today, the work is best known under the title Divisiekroniek (‘Division Chronicle’), but that name should properly be placed between inverted commas. Nowadays, we also have an author’s name, for which we should especially thank an early reader, Jan van Naaldwijk, who tells us that the work was written by one ‘brother Cornelius of Lopsen, regular’; him we believe to know under the name Cornelius Aurelius. The remark, which Jan wrote down shortly after he had first become acquainted with the chronicle, was rediscovered in the nineteenth century, and seized to permanently provide an author to Die cronycke van Hollandt, Zeelandt ende Vrieslant.

And while Aurelius is an excellent candidate for the authorship of the Divisiekroniek, it is not at all clear whether Jan van Naaldwijk based his claim on actual knowledge, or on conjecture; in any case we know for certain that for personal reasons it was expedient to him that via Aurelius, a childhood friend of Erasmus, he was able to link the Divisiekroniek to the group of humanists which had formed around the famous son of Rotterdam. The attribution of authorship blurs our vision on those reasons, and passes by the fact that the great majority of readers of the Divisiekroniek in the sixteenth to the nineteenth century knew the text as a work by Anonymus; it possibly also is a contributory factor to the circumstance that in scholarly publications about the text little attention has been paid to the possibility that the publisher himself thoroughly intervened with the work (see Levelt 2011: 148-68 and Gerritsen 1992).

Sometimes it was individual readers, like Jan van Naaldwijk, who replaced Anonymus with a named author; sometimes such an attribution was shared widely. Thus, virtually every contemporary knew that the anonymously published Weltchronik was the work of Hartmann Schedel (thus, for example, Trithemius 1494: fol. 139v and Anonymus 1517: fol. b.v). Sometimes readers were collectively engaged in depriving Anonymus of the authorship of a work: thus, for example, many readers of Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion (1612), in a large number of extant copies, by hand added the name of the anonymous author of the prose commentary which was printed with the text. When he wrote this commentary, John Selden was a nearly unknown entity; when modern readers of the text write how Drayton for the commentary consulted ‘the great antiquarian scholar’ John Selden (‘the learnedst man on earth’), therefore, they are wide beside the mark. Drayton consulted a promising but virtually unknown young friend, who eventually, partly thanks to the work he delivered, made name. By taking the name of the author for granted, we miss that dimension in our understanding of the text and its history.

Taking into account how widespread anonymous authorship was, it is regrettable that in general, in books about medieval literary theory and ideas about authorship (such as Minnis 1988 and Wogan Brown et al. 1999), the principle is all but ignored; there, the emphasis is especially on the self-confidence and self-knowledge of the medieval author. On the one hand, that is a welcome correction to what came before: the previously widespread assumption that individuality did not exist in the Middle Ages. But it also ignores the interesting dynamic that individuality and anonymity can engage in. The fact that most medieval texts were disseminated anonymously does not detract from the significance of authorship in medieval textual culture, on the contrary: only in contrast with that omnipresent anonymous authorship we can clearly distinguish the contours of known authorship (see, e.g., Unzeitig 2010).

Thus far my plea for the recognition of Anonymus as author; not because the author is dead (Barthes 1967), nor because we have to believe without question Foucault (1969) when he claims that authorship, before the early modern period, was only considered important in relation to works of science, but because we are now – in part thanks to Alistair Minnis (1988) and Jocelyn Wogan-Browne (1999) – thoroughly convinced that authorship has indeed always mattered, but Anonymous nevertheless continued to write with impressive persistence (see North 2003).

For whom this all still does not suffice, this: Anonymus, over time, became known under countless other names, too. Besides Saint Nobody, one of these names is Nameless, who in turn was better known by the name Oursson (Kuiper 2012). Acquaintances of Willem Kuiper know him better by the name Wildeman (‘Wild Man’).** Sufficient reason to pay close attention to the precise role of Anonymus in medieval literature.

* Helen Cooper has recently discussed the consequences of attribution of authorship of Piers Plowman to our understanding of the text in a lecture at the University of Oxford Medieval English Research Seminar, ‘Right Naming in Piers Plowman and the Romances’.

** ‘In De Wildeman’ is the beer tasting bar frequented by Willem with his students and colleagues (http://www.indewildeman.nl/).

Bibliography

Anonymus, Die cronycke van Hollandt, Zeelandt ende Vrieslant, beghinnende van Adams tiden […].Leiden, 1517.

Barthes, R., ‘The Death of the Author’, in: Aspen 5-6 (1967), transl. Richard Howard, n.p.

Bonner, F.W., ‘The Genesis of the Chaucer Apocrypha’, in: Studies in Philology 48 (1951), 461-81.

Drayton, M., Poly-Olbion. London, [1612].

Dumville, D., ‘“Nennius” and the Historia Brittonum’, in: Studia Celtica 10/11 (1975/6), 78-95.

Dunphy, G. (red.), Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Leiden, 2010.

Foucault, M., ‘Qu’’est-ce qu’un auteur?’, in: Bulletin de la Société Française de Philosophie 63 (1969), 73-104.

Gerritsen, J., ‘Jan Seversz prints a Chronicle’, in: Quaerendo 21 (1992), 99-124.

Jacob, de coster van Merlant, ‘Over mijn verzamelde werken’, in: Neder-L 17/1/2000 (http://digitaalarchiefwillemkuiper.blogspot.co.uk/2013/07/neder-l-column-47-over-mijn-verzamelde.html).

Kuiper, W., ‘Die destructie van Jherusalem in handschrift en druk’, in: Voortgang, jaarboek voor de neerlandistiek 25 (2007), 67-88.

Kuiper, W., ‘Valentijn en Oursson’, in: Voortgang, jaarboek voor de neerlandistiek 28 (2010), 213-45.

Kuiper, W., ‘Die historie van Valentijn ende Oursson compleet’, in: Neder-L 28/10/2012 (http://nederl.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/die-historie-van-valentijn-ende-oursson.html).

Kuiper, W., ‘Het dieet van Karel de Grote’, in: Neder-L 7/2/2013 (http://nederl.blogspot.co.uk/2013/02/column-91-het-dieet-van-karel-de-grote.html).

Kuiper, W. & R. Resoort (eds.), Maria op de Markt. Middeleeuws toneel in Brussel. Amsterdam, 1995.

Levelt, S., ‘“This book, attractively composed to form a consecutive and orderly narrative”: The Ambiguity of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britannie’, in: E. Kooper (ed.), The Medieval Chronicle 2. Amsterdam, 2002, 130-43.

Levelt, S., Jan van Naaldwijk’s Chronicles of Holland: Continuity and Transformation in the Historical Tradition of Holland during the Early Sixteenth Century. Hilversum, 2011.

Lie, O. & W. Kuiper (eds.), T. Summerfield (transl.), The Secrets of Women in Middle Dutch. A bilingual edition of Der vrouwen heimelijcheit in Ms. Ghent UB 444. Hilversum, 2011.

Ligota, C.R., ‘Annius of Viterbo and Historical Method’, in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987), 44-56.

Minnis, A.J., Medieval Theory of Authorship: Scholastic Literary Attitudes in the Later Middle Ages. 2e ed., Aldershot, 1988.

North, M.L., The Anonymous Renaissance: Cultures of Discretion in Tudor-Stuart England. Chicago, 2003.

Salomon, R.G., ‘Poggio Bracciolini and Johannes Hus: A Hoax Hard to Kill’, in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 19 (1956), 174-7.

Shakespeare, W. & W. Rowley, The Birth of Merlin, or: The Child hath Found his Father. London, 1662.

Trithemius, J., Liber de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis. Basel, 1494.

Unzeitig, M., Autorname und Autorschaft. Bezeichnung und Konstruktion in der deutschen und französischen Erzählliteratur des 12. und 13. Jahrhunderts. Berlin, 2010.

Wogan-Browne, J., N. et al. (eds.), The Idea of the Vernacular: An Anthology of Middle English Literary Theory. University Park, PA, 1999.