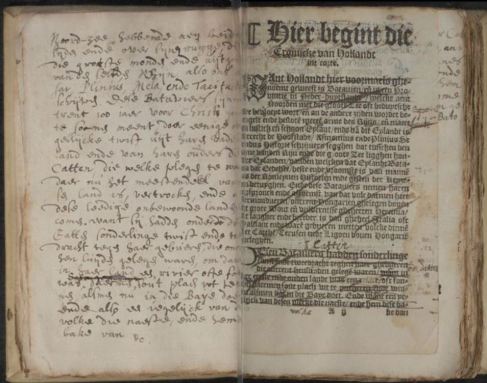

A significant part of my research is devoted to early modern readings of medieval histories. In particular, I have written about how medieval chronicle traditions were continued into the sixteenth, seventeenth and even eighteenth centuries: for example, one chronicle of Holland which I worked on, first printed in 1538, and itself based on a printed chronicle from 1517 which was itself based mainly on late 15th-century sources, was continuously reprinted until 1802, and regularly revised in the process. My book (previews available here and here) concerns the chronicle tradition of the county Holland – a medieval principality which from the 1580s would become one of the seven constituent provinces of the Dutch Republic. When I worked on that chronicle tradition, two aspects in particular stood out for me in the early modern treatments of medieval histories of the county of Holland: firstly, the provincialism so characteristic of the medieval chronicle tradition of the county of Holland was no problem for readers in the Dutch Republic; secondly, neither was its Catholicism. Or so I thought. But the story turns out to be quite a lot more interesting than that. In fact, judging from readers’ responses I encountered since, their Catholicism may for many readers very well have been the very point of reading such histories. I already knew that these works did find a receptive audience among Catholic communities in the Protestant Netherlands: this was indeed one of the explanations I had offered for the popularity of one particular offshoot of the chronicle tradition of Holland, namely that concerning the house and monastery of Egmond. I had found further confirmation of this kind of use of medieval histories in a fascinating early seventeenth-century manuscript (Haarlem, Noord-Hollands Archief, Collectie van losse aanwinsten [inv. 176], no. 1524), which contains excerpts from various (printed) medieval chronicles as well as polemical Catholic works of the early modern period. Such use can also be seen in what is probably the most interesting book I’ve encountered in this context: The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, 393 F 18. It is a printed chronicle of Holland (one of the countless revised reprints of the 1538 chronicle mentioned above), printed in the 1590s but concluding in 1540. The KB copy, however, has been further revised and updated: the printed pages are interleaved with blank pages for corrections and additions to the text of the chronicle, and further blank pages were added at the end, and the chronicle was updated up to 1574 (with one remark postdating November 1588), thus including a report of the early years of the Dutch Revolt. [Update 15 January 2015: the full book can now be viewed, for free, here.]  First, however, the reviser set to make corrections to the original printed chronicle. Most of these are relatively minor: deletions, mostly of matter not strictly concerned with Holland; and substitution of Arabic for Roman numerals.

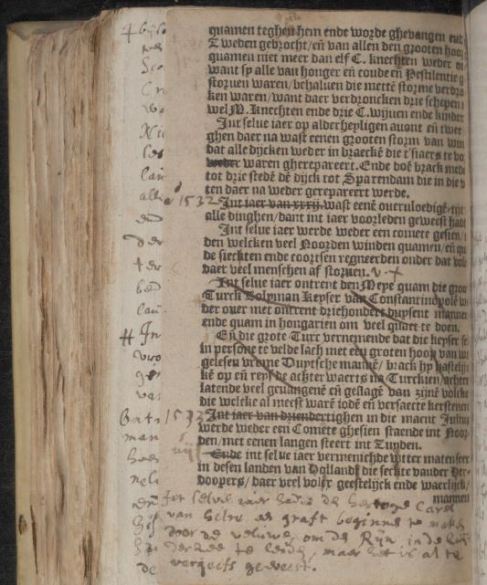

First, however, the reviser set to make corrections to the original printed chronicle. Most of these are relatively minor: deletions, mostly of matter not strictly concerned with Holland; and substitution of Arabic for Roman numerals.  Regularly, however, additional entries of information are also included, or passages are extensively revised. Most of these additions and the continuation, while interesting, do not provide us with much information about their author: the description of an Anabaptist as a ‘false fraud’ and the teaching of Menno Simons as an ‘error’ would be shared by anyone who considered themselves to be anything but a Mennonite or an Anabaptist. Even Martin Luther is described in entirely neutral terms. But occasionally the manuscript gives us clues to the personality of the reviser, whose identity, however, remains unknown. Thus, we can deduce from the language that the continuation is written by an apparent supporter of the Revolt. The sack of Naarden by Don Federico, in 1572, for example, is written in negative terms, and a survival from a burned and collapsed building in the town described as miraculous. Support for the Revolt, however, does not necessarily imply support for the Reformation, and this is where things get really interesting: it appears that the reviser of our chronicle was a Catholic, who attempted to ground the history of the Dutch Revolt on the medieval history of Holland. Some clues are provided by some types of information: thus, the reorganization of bishoprics under Philip II is given much space, including the names of several bishops; the bishops of Utrecht are listed by name up to 1588. While the aims of the revolt are described in positive terms – to ‘expel the Spaniard from this land’ – and the rule of Duc d’Alva in negative terms – ‘oh terrible tyranny’, the writer exclaims (but subsequently deletes) – the narrative is by no means straightforward, particularly when dealing with the first wave of the Inquisition in the Netherlands. While the second wave is dismissed as cruel and cause of great conflict, the same cannot be said for the initial response to the Reformation: especially Ruard Tapper, one of the leaders of the Inquisition during the very early Reformation, is described in very positive terms: he was ‘very famous’, and a ‘staunch defender of the Pope’.

Regularly, however, additional entries of information are also included, or passages are extensively revised. Most of these additions and the continuation, while interesting, do not provide us with much information about their author: the description of an Anabaptist as a ‘false fraud’ and the teaching of Menno Simons as an ‘error’ would be shared by anyone who considered themselves to be anything but a Mennonite or an Anabaptist. Even Martin Luther is described in entirely neutral terms. But occasionally the manuscript gives us clues to the personality of the reviser, whose identity, however, remains unknown. Thus, we can deduce from the language that the continuation is written by an apparent supporter of the Revolt. The sack of Naarden by Don Federico, in 1572, for example, is written in negative terms, and a survival from a burned and collapsed building in the town described as miraculous. Support for the Revolt, however, does not necessarily imply support for the Reformation, and this is where things get really interesting: it appears that the reviser of our chronicle was a Catholic, who attempted to ground the history of the Dutch Revolt on the medieval history of Holland. Some clues are provided by some types of information: thus, the reorganization of bishoprics under Philip II is given much space, including the names of several bishops; the bishops of Utrecht are listed by name up to 1588. While the aims of the revolt are described in positive terms – to ‘expel the Spaniard from this land’ – and the rule of Duc d’Alva in negative terms – ‘oh terrible tyranny’, the writer exclaims (but subsequently deletes) – the narrative is by no means straightforward, particularly when dealing with the first wave of the Inquisition in the Netherlands. While the second wave is dismissed as cruel and cause of great conflict, the same cannot be said for the initial response to the Reformation: especially Ruard Tapper, one of the leaders of the Inquisition during the very early Reformation, is described in very positive terms: he was ‘very famous’, and a ‘staunch defender of the Pope’.  The reader who would be interested to hear more about the ‘devout deeds’ of the leader of the first wave of the Spanish Inquisition in the Netherlands is referred to the Inquisitor’s own autobiographic (and hagiographic) writing, the Apotheosis. For some readers, the very point of reading medieval chronicles in the early modern period was their Catholicism. And this was not only the case for Catholic, but also for some Protestant readers, if in a diametrically opposed fashion. Such a response can be seen in a book in the Bodleian Library, H 1.8 Art.Seld., a 1591 edition of the 1517 chronicle of Holland which had been the source of the shorter chronicle from 1538. According to an ownership mark, the book once belonged to one Johan van Valckenburgh – possibly to be identified with the military engineer of that name (c.1575–1624) who was in the service of Maurits of Orange.

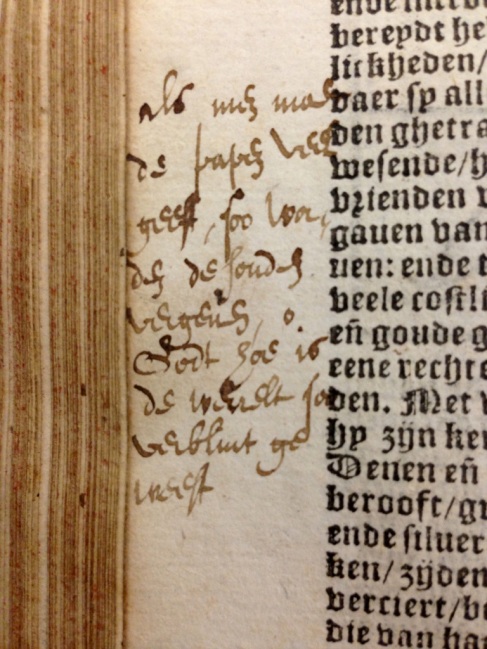

The reader who would be interested to hear more about the ‘devout deeds’ of the leader of the first wave of the Spanish Inquisition in the Netherlands is referred to the Inquisitor’s own autobiographic (and hagiographic) writing, the Apotheosis. For some readers, the very point of reading medieval chronicles in the early modern period was their Catholicism. And this was not only the case for Catholic, but also for some Protestant readers, if in a diametrically opposed fashion. Such a response can be seen in a book in the Bodleian Library, H 1.8 Art.Seld., a 1591 edition of the 1517 chronicle of Holland which had been the source of the shorter chronicle from 1538. According to an ownership mark, the book once belonged to one Johan van Valckenburgh – possibly to be identified with the military engineer of that name (c.1575–1624) who was in the service of Maurits of Orange.  Again we have a later reprint of a late medieval chronicle of Holland, and again we find manuscript additions; here, however, these remain limited to occasional annotations in the margins. The annotator in this case, however, was clearly anti-Catholic, and most of the annotations serve to dismiss ‘fables’ of the ‘papists’, and to call extra attention to narratives of corrupt and heretic popes and the like. ‘Oh God,’ our annotator at one point exclaims, ‘how can the world have been so blinded?!’

Again we have a later reprint of a late medieval chronicle of Holland, and again we find manuscript additions; here, however, these remain limited to occasional annotations in the margins. The annotator in this case, however, was clearly anti-Catholic, and most of the annotations serve to dismiss ‘fables’ of the ‘papists’, and to call extra attention to narratives of corrupt and heretic popes and the like. ‘Oh God,’ our annotator at one point exclaims, ‘how can the world have been so blinded?!’  Indeed, the negative sentiments aroused by the chronicle seem to have been a source of a certain titillation; in this case it was not the Catholic heritage of the middle ages, but this excitement aroused by Catholic narratives, which made the medieval chronicle so appealing to this early modern reader.

Indeed, the negative sentiments aroused by the chronicle seem to have been a source of a certain titillation; in this case it was not the Catholic heritage of the middle ages, but this excitement aroused by Catholic narratives, which made the medieval chronicle so appealing to this early modern reader.  This latter type of response is in fact a frequent occurrence in early printed chronicles; another example is found in an English chronicle in the Bodleian Library (F 2.27 Art.Seld., a copy of the English translation of Higden’s Polichronicon, printed in 1515 by Wynkyn de Worde), where in the table of contents the word ‘pope’ is consistently crossed out – ‘Adrianus pope / Johannes the .xxi. pope / Nicholaus the thyrde pope

This latter type of response is in fact a frequent occurrence in early printed chronicles; another example is found in an English chronicle in the Bodleian Library (F 2.27 Art.Seld., a copy of the English translation of Higden’s Polichronicon, printed in 1515 by Wynkyn de Worde), where in the table of contents the word ‘pope’ is consistently crossed out – ‘Adrianus pope / Johannes the .xxi. pope / Nicholaus the thyrde pope‘ –, a reminder that even the most innocuous additions of readers could be crucial evidence to perceptions of texts.* It is a response perhaps similar to the deliberate scratching out of eyes in frescoes in Anatolian Churches. Such occasions of targeted destruction are, in fact, evidence of serious engagement with a culture perceived as ‘other’ by the vandal. As such, they form important evidence not only for early modern readers’ responses to medieval histories, but for their interaction with the world around them. . Images used with kindest permission from the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague (images from Early European Books) and the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. . . * @EdvanderVlist kindly suggested to me that the deletion may have had to do with legislative efforts under Henry VIII to have references to Catholic icons such as Thomas Becket and the pope ‘rased and put out of all the bokes’ (thus in a decree from November 1538). This suggestion led me to this excellent article, by Dunstan Roberts, to whose evidence illustrating that many readers went ‘beyond the minimum requirements of the legislation’ the Bodleian Polychronicon can be added. I agree with him that such books appear to show that ‘the owners of books developed the habit of crossing out words on an almost systematic basis.’

Tag Archives: palaeography

Early modern/medieval histories

Filed under #MedRen

#1stMS

In October I tweeted a picture from the very first medieval manuscript I ever called up in a special collections reading room: a small, charmingly illustrated collection of Marian prayers. Once I had sent the tweet, I thought it was interesting that I remembered the manuscript so well: I had only seen it once, and never extended my acquaintance beyond the one meeting. That this manuscript had been my ‘first’ was also more or less a coincidence: I had developed an interest in medieval studies in the first two years of my undergraduate studies in Dutch language and literature, and was spending a year in Berkeley as exchange student. The only manuscript in Dutch I could find was this little devotional work; I made a transcription of a couple of pages, admired the beautiful illustrations, and that was that.

https://twitter.com/SjoerdLevelt/status/391342490118139904

I had seen manuscripts before, and even held some in my hands: the year previously I had taken a codicology course taught by Jos Biemans, who had shown us several manuscripts of the University of Amsterdam Library, including its famous Caesar De bello Gallico manuscript. He let us touch the books he took into class, too, convinced that that was the best way to get us to appreciate the physicality of the codex. By the end of the course we had been so immersed in medieval manuscripts, that when he showed us a slide of one and asked us to date its script, it took a couple of minutes for the first of us to realize that we were looking at a faux-Gothic Asterix Christmas card (I wish I could show you the picture, but I have never been able to find it – so please send it to me if you have it).

But there is something special about that very first, one-on-one, encounter with a manuscript of your own choosing, called up to the manuscript reading room for your own consultation. Something so special that, in fact, I suspected we all remember our first manuscript. So I tweeted this question:

https://twitter.com/SjoerdLevelt/status/391494305673936896

The question was picked up by a number of great manuscript tweeters (such as @peripheralpal and @erik_kwakkel), and soon my suspicion was confirmed, but the responses did something more than that; they also showed a little bit why exactly it is that we remember that particular manuscript.

For a few of us, experience with manuscripts came long before we started studying history (‘Actually I met manuscripts much earlier, when I read from sifrei torah (handwritten Bible scrolls) as a teen’, writes @andrea_a_l). Many of us called up our #1stMS for a palaeography or codicology course as undergraduates or postgraduates, or in summer school, for an exercise in description, although for several of us the first time we called up a manuscript came once we had started our PhD research. Many come to their #1stMS with a specific research question, in the context of MA of PhD research, or for a job: certain prayers in a particular manuscript; descriptions of virtues in the middle ages; manuscripts containing a particular text; in search of evidence a specific correction of a text; descriptions of manuscript fragments, and so on.

While many first encounters did not result in long-term engagement, others did. In one case, the manuscript was ordered up in search for an MA subject, and while not used then, was revisited later for other research. The encounter is always impressive, if perhaps not just enough for a change of career plans – although @onslies, an early modernist who asked if she could come and play with us wrote of her first medieval manuscript that it ‘is gorgeous and made me regret not being a medievalist’.

Sometimes, the first experience of a manuscript is via substitute such as microfilm or digital scan; nevertheless, one can build up such a level of knowledge of a manuscript via this route that it counts as the real experience: this was the first manuscript I knew. That said, the first actual meeting with the manuscript can lead to some pleasant surprizes: @pabinkley writes about his #1stMS that its previous ‘editor used rotographs, which didn’t reproduce blue: I was surprised to find the “missing” initials intact’. And we remember other lovely details, too: a ‘nice doodle of a face on f. 1’ (@CarrieGrif), ‘this furious monk’ (@HLaehnemann), a ‘glorious portrait of female patron Joan Tateshal’ (@andrea_a_l). There are also chance encounters which linger in memory: ‘Letter Book G at Royal Society, looking for a letter from de Graaf. Open book, 1st document is a letter from Galileo!’ (@matthewcobb).

Some first manuscripts are very impressive; first prize should perhaps go to @Codicologist (then @GeekChic83), who sat down with the Exeter Book – although the real prize was of course the manuscript itself: ‘Best 10 hours of my life so far!’ But a manuscript does not have to be quite as famous as that to leave an equally lasting impression: @sarahxgilbert’s 1stMS was ‘an orphaned, scruffy flyleaf with some medical recipes. I felt very lucky to visit it’. That first encounter is often followed by lasting warm feelings: ‘Still in love with it’ (@KKrick11); ‘Still fond of all three!’ (@LucyAllenFWR). Sometimes, however, the sentiment is one of enduring perplexity: ‘I checked it again last month and it’s still a puzzle’ (@DanielWakelin1).

The meeting with a manuscript is a very physical experience – and indeed there are goose bumps and sweaty hands all around, as well as reminiscences of the smell of the manuscript. To return to the Exeter book: ‘The best thing about handling the Exeter Book was seeing gold flecks on parchment from where MS was used to keep gold leaf flat. You don’t get that with the (excellent) facsimile or dig. ed. Goose bump moment when the light hit the parchment just right!’ And the physical responses do not end with that first encounter, but continues when later revisiting the same manuscript: ‘ordering that #1stMS gave me again the buzz of years ago!’ (@onslies); Kathleen Neal can ‘still remember the awe & the lovely smell!’ (via @MonashCMRS). The digital, however, is encroaching: some visited their first manuscript in order to digitize it, others report that their #1stMS has now been digitized. It seems to be with a certain level of satisfaction that one reports that their #1stMS is ‘still not available on @GallicaBnF’.

Many share memories of lovely and knowledgeable librarians (@bodleianlibs and @ExeterCathedral are singled out for praise), although some (not to be identified here) are a little less nice: @skatemaxwell reports, after being granted permission to see a prestigious manuscript at a famous library in France, being asked ‘by horrified librarian ‘Mais qui êtes vous?!’’; @rebeccadixon75 had her #1stMS actually snatched from her hands when librarians recognized their error of giving a restricted manuscript to a lowly MA student.

Reminiscing about our #1stMS naturally also leads us to reminisce about our teachers of codicology and palaeography, and share fond memories. Jos Biemans, J. Peter Gumbert, John Higgitt and Malcolm B. Parkes are among the eminent palaeographers mentioned. Special credit goes to Steven Justice and Jennifer Miller of the University of California at Berkeley, who even visited their student (@adrienneboyarin) in the reading room ‘to coach on basics, calm nerves. I’d do it for any student now’. Similarly, and also at Berkeley, Alan Nelson provided a special kind of encouragement: ‘he didn’t tell me it was unusual for a US undergrad to transcribe 138 ff. of late Middle English…’ (@skgoetz). It seems that for many of us, our #1stMS experience was also a moment we became a little more aware of didactic approaches, and perhaps a moment that brought us a little closer to our teachers; in any case, we have taken from the encounter some of our teachers’ techniques: ‘he made us (3rd y students) each look at one aspect of the newly bought ms … brilliant way of teaching mss!’ (@HLaehnemann); others report that they now use the very same manuscripts they were taught with to teach codicology to a new generation of scholars.

.

.

With many thanks to the following for their contributions to #1stMS: @1greenblogger, @abilglen, @AboBooks, @aclerktherwas, @AdrienneBoyarin, @andrea_a_l, @b_hawk, @Bertilak, @CarrieGrif, @chaprot, @Codicologist, @DamienKempf, @DanielWakelin1, @DenizBevan, @DirkSchoenaers, @dongensis, @dorothyk98, @erik_kwakkel, @gerardfietst, @GingerMarple, @HLaehnemann, @homophonous, @jessehurlbut, @JohanOosterman, @katemond, @KKrick11, @KLaveant, @krijnpansters, @krmaude, @LeaFantastica, @lisafdavis, @lmeloncon, @LucyAllenFWR, @MariaRottler, @matthewcobb, @MedievalMcCoy, @meganlcook, @melibeus1, @MFLCOF, @MonashCMRS, @moselmensch, @mtechman, @ncecire, @NotThatJHendrix, @onslies, @pabinkley, @peripheralpal, @Prossian, @protoDW, @Quadrivium_UK, @RabiaGregory, @RandallsCottage, @rebeccadixon75, @RMBLF, @RNAmendola, @robmmiller, @sarahxgilbert, @skatemaxwell, @skgoetz, @susuer, @SvenMeeder, @Zweder_Masters. I am grateful to @Codicologist for reading and commenting on a draft, and to @Quadrivium_UK for hosting this post.

Finally, special thanks to the original makers of our #1stMSS, and to the institutions who keep them safe: Arnhem, Provinciaal Gelders Archief, 2; Berkeley, @bancroftlibrary, UCB 082 & UCB 092; Bernkastel-Kues, Codex Cusanus 106; Brussels, @kbrbe, 19607; Cambridge, @theUL, Ee.1.12 ; Chapel Hill, @UNCLibrary, 522; Douai, Bibliotheque, 167; Dublin, @RIAdawson Library, D II 3; Exeter, @ExeterCathedral Library, 3501; Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, XC sup.; Innsbruck, Universitätsbibliothek, 900; Iowa City, @UILibraries, c36li; Leiden, @ubleiden, BPL2627 & LTk 278; London, @BLMedieval, add 47059, add 30863, add 33241, Cotton Nero D. IX, Cotton Tiberius A. xv, Cotton Vespasian D. v, Egerton 1151, Egerton 827, Harley 3865, Harley 4482, Sloane 1686, Sloane 3466; London, @royalsociety, Letter Book G; London, @WellcomeLibrary, 46; Madrid, @BNE_biblioteca, 5254; New York, @MorganLibrary, 691; Oxford, @bodleianlibs, Ashmole 61, Douce 215, Douce 252, Douce 324, e Museo 35, Fairfax 40, Hatton 31, MS Eng. letters e. 29, Rawlinson B 505; Paris, @ActuBnF, fr. 12476, fr. 1584, fr. 22928, lat. 14503, lat. 15962; Philadelphia, @upennlib, Codex 196; Princeton, @PrincetonPL, Taylor 1 (Phillips 2223); Providence, @brownlibrary, French translation of Ludolph’s Vita Christi; Strasbourg, Bibliothéque Nationale et Universitaire, 0309; Utrecht , @UniUtrechtLib, 315; Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Lat. 3822; Zutphen, Regionaal Archief, Antiphonarium of the St. Walburgis church.

Filed under #1stMS